DurationWhere a note is placed on the staff and its letter-name will tell us how high or low the pitch of the note will be, but how do we know how long we should play it? After all, some notes in a piece of music sound for a long time while others are very short before we move on to another note.

We can tell how long to play a note by seeing how the note looks. Here are some different notes:

These different shapes tell us how long or short to play each note. Where the note is on the staff tells us the pitch of the note, but its shape tells us how long to play it.

You probably have heard people talk about keeping the beat in music. The beat is how we count while we play and is what helps us know how to fit in the different note lengths in the music we’re playing. In what is called “common time,” we count to four steadily over and over: 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 , 1 – 2 – 3 – 4. (Later we will learn how fast or slow to count these beats, but whatever speed we use must be steady and constant, like a pendulum on a clock.)

The note that looks like an egg (the first note in the illustration above) is called a whole note. This note gets four beats or counts, so when we play a whole note we make the note sound while we count to ourselves 1 – 2 – 3 – 4. The second note above is a half note. It looks like a whole note except that it has a stem attached to it. The stem may point up or down, but that makes no difference. A half note is played for half the length of a whole note. If we divide four in half we get two. So this note is played for only two counts: 1 – 2. The third note, which looks like a half note except that the head or round part is black, is a quarter note, and it cuts a half note in half, so that it is held for only one count. The notes that follow the quarter note in our example each cut the note in front of it by half by adding one or two flags onto the stem. We won’t worry about those now. Right now we will only think about whole notes (4-count notes), half notes (2-count notes), and quarter notes (1-count notes).

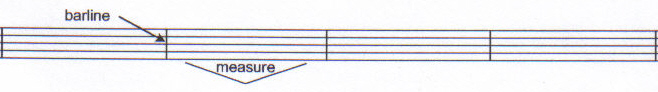

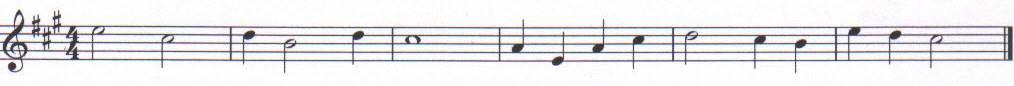

At the beginning of a piece of music you will see some numbers on the staff. These numbers are called the time signature, and they tell us how we are to count the beats in the music. You also will see that the staff is divided by vertical (up-and-down) lines at various places. These are called barlines, and they break up the staff into measures. The space between two barlines is one measure. The numbers at the beginning of the staff tell us two things: the top number tells us how many beats we will have in each measure; the bottom number tells us what kind of note will get one beat. For instance, if the numbers are 4/4, that means we will count to four in each measure, and a quarter note will get one beat. (For now we will only think about quarter notes, so the bottom number will always be 4, which means the black note with a stem will always be equal to one beat.)

In 4/4 time (which is also called common time) every measure of music must have a total of four beats. That means all the notes in the measure must add up to four ... no more, and no less. Since a whole note equals 4, a half note equals 2, and a quarter note equals 1, we can mix them up in different ways, just so long as all of them combined add up exactly to four (the number of beats in the measure). There may be only one note (a whole note) which by itself equals four, or there may be as many as four quarter notes (1 + 1 + 1 + 1 = 4). Here are some different ways we can fill up a measure in 4/4 time: