St. Oswin of Deira

King and Martyr

EDITOR’S NOTE: Almost everything that is known of the life of St. Oswin was penned by an anonymous monk of Tynemouth sometime shortly after the Saint’s death in 651. Bede references this biography in his Ecclesiastical History. What follows is an abstract of the life of St. Oswin of Deira, taken from a biography by John Henry Newman published in Lives of the English Saints in 1844. As Newman wrote with a very Victorian pen, a few small editorial changes have been made in the following account in an effort to make it more readable to the contemporary eye.

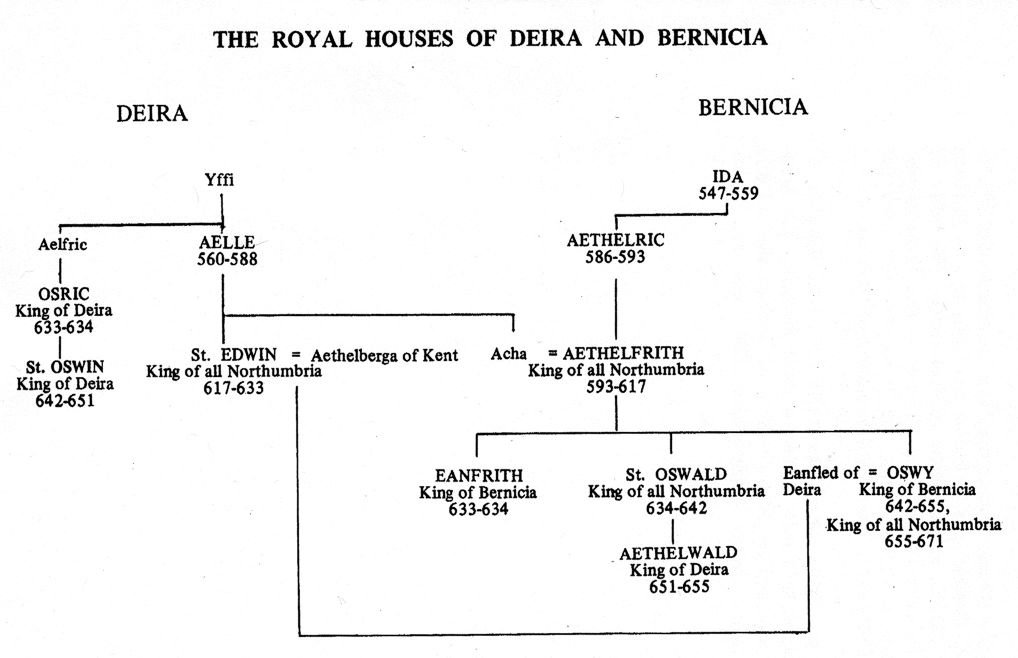

Oswin was the son of Oswic king of the Deiri, the monarch who unhappily apostacized from the faith, and was afterwards slain by the bloody Cadwalla of Cumberland. At the time of his father’s death, Oswin appears to have been quite a child so that, being beneath the notice of the vindictive conqueror, his friends managed to carry him off among the West Saxons. It would seem that he was baptized while young, either before his father was slain or when he was first taken among the Christian subjects of Kinegils. He lived in exile for ten long years, greatly edifying those among whom he dwelt. He was very beautiful, tall of stature, and of a particularly engaging address; but these things, which to most young men are calamities as being so many occasions of falling, he turned to the glory of God. Among other virtues he was so conspicuous for the grace of chastity that his biographer compares him to Joseph while dwelling among the Egyptians. Among posterity generally his more especial grace was thought to be humility: and indeed it was very observable how intimately connected a lowly mind seems to be with pure thoughts, so that one virtue appears to follow as a consequence upon the other. For bashfulness which is the shield of purity is close upon humility.

Like so many other of the Saxon kings, Oswin learned the art of reigning in the school of exile. After the death of St. Oswald, Oswy became king of the Bernicians; Oswin returned from exile, and either by Oswy’s adoption, as some say, or by the election of the nobles, according to others, was raised to the throne of the Deiri. When we come within the sphere of the Church, how the jarring sounds of earthly strife seem all stilled! Saint reigns after Saint among the Northumbrians, yet the reign of one is the exile of the other; the term of power with the one is exactly the term of depression with the other. Yet the exile is God’s school: There the Saint was made, and Oswald seems as it were the stern author of the sanctity of Oswin. So it was with Oswald himself: The death of the blessed Edwin opens the gates of his native land to the fugitive prince, the future king and Saint....

The secular details of Oswin’s reign are not preserved to us; doubtless they were full of that consistency and sagacity which high principals invariably displays. The general results, however, are told us; they were peace, order, and the happiness of those beneath his sway. We may be sure also that ecclesiastical matters prospered under his care, for there existed the closest friendship between the sovereign and the holy bishop Aidan. Oswin’s biographer, the [anonymous] monk of Tynemouth, beautifully exclaims, “O man full of piety! O worthy of a crown! In that time the most blessed bishop Aidan ruled with his pastoral care the province of the Northumbrians. He was a Scot by birth, catholic in his faith. St. Oswald the king had raised him to the episcopate, and by his preaching Divine grace had converted no small number of the people to the faith of Christ. It was this holy man’s custom to teach the people committed to his charge, not in the Church only, but seeing how tender the young faith yet was, he went about the province entering the houses of the believers and sowing the seed of the divine word in the field of their hearts, as each one was able to receive it. This man, so careful of the flock entrusted to him, used often to come to St. Oswin king of the Deiri and stay with him on account of the sweet odor of his sanctity. He admonished him to persevere in good works, and always to be advancing to better things and the summits of perfection, and, taught by the Holy Spirit, he forewarned him how that he must pass to the heavenly kingdom through martyrdom. The king, receiving him as a Saint, gave diligent heed to his preaching the words of life; and holding himself in devout subjection to that most beloved father, he corrected at his reproof whatsoever he had done amiss. The bishop indeed was beyond measure delighted with the humility and obedience of the king and often held familiar converse with him about the contempt of the world, the sweetness of a heavenly life and the glory of the Saints. The king was by no means a forgetful hearer of the word of God, but a zealous doer of the same; and according as he had learned from his good master, he took care of all with a fatherlike affection, feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, and bestowing favors with alacrity upon all who asked them. There was between them such a confederacy of mutual love that the king held the holy bishop for an Angel and obeyed his suggestions as though they were inspired. The bishop on the other hand loved the king as though he were part of his own soul, one while upbraiding him as a son if he were too much occupied, as men are wont to be, in secular matters, another while cherishing and inflaming him like a dear friend with spiritual conversation.”

A most beautiful example of this intercourse between the bishop and the king has been left on record for our edification. We have already alluded to St. Aidan’s custom of making circuits through his diocese and entering houses and catechizing. These pastoral journeys he mostly performed on foot, after the example of our Blessed Lord, of whom we read only once that He rode upon an ass, entering His own city in such meek triumphal guise that the prophet’s words might be fulfilled. Personal fatigue and hardship and what the world would call loss of time were not the only disadvantages which the holy prelate sustained. The frequent rivers and streams of the northern shires of England, for the most part rapid and stony, were to be forded often at the risk of life.

To save the bishop from this peril, as well as to lighten his labors, Oswin made him a present of a very valuable horse, which St. Aidan accepted. Possibly the bishop put less value upon it than the king, for riding would not be so favorable as walking to the constant self-recollection and mental prayer which he doubtless practised on his journeys, making the intervals of passage from place to place in some measure to compensate the loss of that former monastic leisure which he had cheerfully given up for the edification of his neighbor. However this may be, Oswin’s horse did not stay long with St. Aidan. For soon after the present had been made, the bishop, mounted on his horse, adorned with rich and royal trappings, met a beggar who asked him for an alms. The Saint with the utmost alacrity dismounted from his steed and presented it with all its furniture to the poor man.

Either that day or shortly afterwards St. Aidan was to dine with the king. Before dinner someone told Oswin of what was perhaps considered the slight put by the bishop on the royal beneficence. As they were going to the banquet Oswin said, “My Lord Bishop! Why did you give to a poor man that royal horse which it was more fitting to keep for your own use? Have we not plenty of horses of less price and of commoner sorts which would have been good enough for gifts to the poor without your giving them that one which I had particularly selected for your own possession?”

Whether the king spoke as if nettled by the apparent slight, or complaining as if hurt by the want of attachment shown in parting so lightly with a friend’s gift, we are not told; but the bishop was ready with an answer: “What is that you say, O king? Is that foal of a mare dearer to you than that son of God?” (meaning the beggar).

It would seem from the narrative that Oswin was somewhat out of temper, and was brooding over the matter in his mind. For when they entered the banquet-room the bishop went and sat down in the accustomed place, while the king, who had just returned from hunting, stood and warmed himself at the fire. Perhaps there was something of an inward struggle going on. If so, it soon was over; for as he stood by the fire he pondered the bishop’s words, and suddenly ungirding his sword and giving it to a servant he fell down at St. Aidan’s feet and besought his forgiveness.

“Never again,” said the humbled king, “will I say any more of this, or take upon myself to judge what or how much of my treasure you bestow upon the sons of God.”

The bishop was much moved, and starting up he raised his sovereign, declaring that he was entirely reconciled to him, and begging that he would be seated and enjoy the banquet. Oswin did as the bishop said, and with the elasticity of spirits which ever follow close upon humbling ourselves to confess what we have done wrong, the king grew merry at the feast.

But the countenance of the bishop saddened, and the more lighthearted the good king became, so much the more was St. Aidan lost in silence and sorrow and kept shedding tears. It chanced that a priest sat near, a Scot, who asked his bishop in the Scottish tongue (which the king did not understand) why he wept. “I know well," said Aidan, that the king will not live long; for never have I seen before a prince so humble; wherefore I feel assured that he will soon be taken out of this life, for this nation is not worthy to have such a sovereign.” This, whether it were prophecy or that foreboding which men seem naturally to have when they look on great goodness, was too truly fulfilled....

Oswin’s biographer goes on to say that there were on record many other examples of his great humility, but that he will not relate them lest he should dwell too much on one of his virtues to the depreciation of the rest. One may regret that the good monk has robbed us through such an ill-founded apprehension. Next to humility, mercifulness, not only in the giving of alms but in what often involves greater self-sacrifice and patience and alacrity — in succouring the oppressed. At the same time he exhibited firmness and even forwardness (acredo) in representing those who were disobedient to his laws. Neither were the interior exercises of a spiritual life forgotten; he watched, he fasted, he prayed; and it was in those things and out of those things that he got his humility. Such were the virtues with which “that soul devoted to God was green as the spring, becomingly and abundantly.”

It would appear as if Oswy almost from the very first found it hard to brook the division of the kingdom, which the rule of St. Oswald had molded into one. If then it were he who raised Oswin to the throne of the Deiri, he must have quickly repented of his own measure; or if the elevation of our Saint were owing to the election of the nobles, it was probably distasteful to Oswy at the outset, but that circumstances controlled his opposition or made it necessary for him to dissemble. The very sanctity of Oswin, being in the mouths of all, Bernicians as well as Deiri, was gall to Oswy and fostered his malignant envy. As the monk words it, Oswy tried the serpent, before he took to the lion. In other words, he endeavored for long to compass the death of Oswin by subtlety. But the love and fidelity of all around him was a shield which the dagger of the assassin could never penetrate. Sometimes the schemes of Oswy were detected or anticipated by the shrewdness of his intended victim; at other times Oswin was warned of them by the very men who were compelled to act as the instruments of Oswy. Thus passed seven years of outward peace and outward glory for Oswin; but we learn from this that even the throne was as it were a school of affliction. The continual sense of insecurity, the harassing continuance of suspicion, the weary diligence of warding off blows, the restlessness of being on the watch, the wretched feeling of having ONE enemy, of being a hunted thing -- such was the ermine which lined St. Oswin’s crown; the very kind of life which God gave his servant David wherewithal to sanctify himself.

It is said that the reverence, which the character of St. Aidan compelled even from the dark-minded Oswy, was the main cause that for seven years outward peace was kept. Two years followed of still greater trials for Oswin. We are not told why; only it is recorded that these two years were more troubled than the foregoing ones: Possibly the impatience of envy was unable to wear its disguise any longer and broke out into more frequent displays of malignity. Besides which Oswy was enraged at being baffled by the sagacious gentleness of his enemy, and in half abhorrence of his own meanness took refuge in the more masculine wickedness of open rage. To borrow the monk’s similitude of the animals, weary and ashamed of crawling he resolved to roar and to devour; and at last he gathered together an army for Oswin’s destruction.

Oswin likewise collected some forces, but so inconsiderable that it would appear as though he came rather to deprecate war than to make it. He met Oswy at Wilfar’s Hill, about ten miles from Catterick, near the pleasant Swale, in whose clear waters St. Paulinus has baptized the Saxon peasantry of Yorkshire. Seeing the inferiority of his forces and yet their desperate resolution to sell their lives for their king, and considering that it was personal affection to himself which animated them, Oswin paused. The bloody slaughter which must ensue overshadowed his gentle spirit, and he could not endure to be the cause of death to so many, whether of his own little chivalrous band, or of his foes. He therefore determined to withdraw from the field and disband his troops.

If it was his own crown which Oswy wanted, it was not much for him to resign it and live in obscurity; but if it were his life as well as his crown, why then, if we live we live unto the Lord, and if we die we die unto the Lord; therefore he could part with that also. He called his little army together and spoke to some such effect as this; I say, to some such effect, for the monk’s narrative seems a little more florid than the original legend probably was.

“I thank you, my most faithful captains and strenuous soldiers, for your goodwill towards me; but far be it from me that for my sake only such danger should be run by you who from a poor exile made me into a king. I prefer therefore to return into exile, nay, even to die, than to hazard so many lives. Let me in peace, and not in war, embrace the divine sentence against myself, conveyed to me by the mouth of the blessed bishop Aidan that through martyrdom must I enter the joys of heaven. I refuse not to end my earthly life in such order and time as Christ shall will.”

The soldiers, seeing how earnestly their king coveted to depart and be with Christ, were wounded “with a deep wound in their hearts,” and all with one accord went down on their knees before him and wept and prayed to fight for him. “Haply we may conquer; we may break even through yon wedges of men; but if not, let us die, and not pass into a proverb as deserters of our king.”

But Oswin was unmoved. He saw that it was himself and not his people who were aimed at, that Oswy would not ravage the country or oppress the people even for his own sake, and that by forbidding the battle he was not abandoning his subjects to the horrors of a cruel invasion. He explained this to his men, and concluded by saying, “I pant after martyrdom and the joys of the heavenly kingdom.”

When he had said this, he prayed solemnly to God and said, “Father of mercy and God of all consolation, whose Son is the Angel of great counsels, whose Spirit is the Comforter in difficulties, grant me in this strait to choose the better way. For if I fight, I shall be guilty before Thee of the shedding of blood. If I fly, I shall be counted to have degenerated from the nobility of my parents, and to have fallen short of my station. Flying, I displease men: fighting, I am displeasing unto Thee.” And so, says the monk, he fixed his anchor in God.

Oswin, disbanding his forces, chose one companion of his exile, a faithful adherent named Tondhere, the son of Tylsius. With him he passed that evening from Wilfar’s Hill to the village of Gilling on the west border of Yorkshire, which lies in a green and blythe valley of considerable depth, not far from Richmond. The estate, or, to use a later word, the fief of Gilling, he had lately conferred upon Count Hunwald as one of his most attached courtiers; and that he should turn out a traitor proves in what a state of insecurity Oswin must have passed his days and how completely the meshes of his enemy encompassed him round about. So true it is, as with their Head, so with the Saints, their foes are they of their own household, and their wounds are received in the house of their friends. It is not probable that Oswin expected to escape death, though it was his duty to shun it; for all that he said showed him to be completeley and calmly possessed by the presentiment of its nearness. Hunwald received him into his house, and promised to conceal him.

Meanwhile Oswy was not altogether satisfied. True it was that he was master of the kingdom of the Deiri without opposition: But was his usurpation likely to be stable while one so ardently beloved as Oswin was lying somewhere in exile? And was not his own personal hatred to be satisfied? Of truth he had been balked of half his prey. He therefore commissioned Count Ethelwin, one of his officers, to take a troop of soldiers, seek for the fugitive king, and kill him. The search was not long, for the detestable Hunwald betrayed his guest. Ethelwin surrounded the castle with his soldiers in the silence of the night while Hunwald was paying the homage of his lips to his kind master. Ethelwin entered and notified to Oswin the fatal sentence of the conqueror. At first the king was disturbed with the suddenness of the event and the additional distress of having been betrayed by one under such great obligation to him.

But, recovering his calmness and his dignity, he fortified his breast and tongue with the sign of the Cross, and said to Ethelwin, “The sentence of your king depends upon the permission of my King.” He entreated the count to spare the life of his faithful servant Tondhere; but he refused to survive his master. Both were slain together, and buried together, at Gilling on the 20th day of August, 651, A.D.

So far as appears, St. Oswin remained unmarried. We may suppose that one who all his life long so earnestly coveted the best gifts was not likely to be without a holy ambition for the coronal of virgins, and that in virginity, that great fountain of almsgiving and preceptress of humility, his holy soul would much delight. There are some of the Saints whose lives seem to have been molded by a heavenly vision or some supernatural intimation of their own destiny. This touch of the invisible world appears to draw them apart, to give a direction to their lives, a tone to their character, to be to them as it were a kind of individual sacrament vouchsafed to them. They seem to sit all their days beneath the shadow of this sacred revelation and to sanctify themselves in its secret presence. Perhaps too it will be generally found that the Saints whose lives have this peculiar feature most strongly (for in its measure may it not be the portion of all great Saints?) have been more especially distinguished by humility and a monk of Tynemouth. “The martyr in his glory still invites the wealthy by his example to the tranquil joys of paradise. For he did not attempt the way of sanctity, compelled by the urgency of poverty, or, as men are wont, by the feebleness of ailing health; but, freely drawn by the sole contemplation of the Creator, he lived in the purple of a king, as David did, poor and sorrowing; poor in spirit even while he abounded in the wealth and delicacy of a monarch; sorrowful in spirit, because he trusted not his heart to his abundance of good things. For the more he abounded, the less desire had he for his abundance. In the midst of a noisy court, which was ever too much for him, he fled far off, and remained in the solitude of his mind, even when his subjects thronged about him. Abroad he carried himself in a kingly way, but inwardly he was a king over his own affections, courageously exercising himself in the love of humility and poverty. He girded himself up to all spiritual exercises, but seemed to pour out his whole being in the corporal works of mercy. His plenty was the needy man’s supply: The superfluities of the rich he deemed the necessaries of the poor. He thought a king owed most to those who could do least for him, and that justice was meant specially for the oppressed. And so was the holy king Oswin, because his people deserved not such a lord, slain by the sword of envy, and translated to the companies of the blessed Angels.”

Very many graces are said to have been granted at the tomb of the royal martyr and through his potent intercession. A life of St. Oswin would be scarcely complete if some mention was not made of these.... We proceed then to relate three miracles which particularly exemplify this. Let it be remembered that by miracles men are not only helped, but they are also taught....

There was a man or Norwich who had a profound reverence for the holy places where our Lord had trodden, spoken, and acted when on earth. Three times did his pious thirst after those far-off fountains of prayer and tears drive him over land and sea to Jerusalem, long, arduous, perilous as the pilgrimage was. Returning home after his third visit, he determined to go northward to pay his devotions at St. Andrew’s in Scotland, a place then regarded with singular veneration. He had, from long usage, become so accustomed to foreign diet thet the rough cheer of English plenty threw him into a violent illness; this was accompanied every fifteen or sixteen days with excruciating spasms, and to gain relief from these seems to have been one, though not the sole, object of this fresh pilgrimage to St. Andrew’s.

On his journey he passed through Newcastle-on-Tyne. In that town dwelt a man named Daniel, whose wife was a very godly woman and specially devoted to the entertainment and care of strangers; for which purpose she had built a house apart from her own dwelling. Here she received the Norwich pilgrim and ministered to him with her own hands; and here he was seized with his fit of spasms. It wounded the heart of his hostess to hear how the poor pilgrim filled the house with his pitiful cries. She consoled him to the best of her power and furnished him with such comforts as she could, till after long agony his exhausted body found a little respite in sleep.

In his sleep he dreamed a dream, or saw a vision. A man of reverend countenance appeared to him and asked him if he wished to recover from his sickness. “Yes, sir,” he replied, “I covet it ardently”" “Rise then in the morning,” was the answer, “and hasten to St. Oswin, the king and martyr, so that on Tuesday next you may be present at the feast of the Invention of his relics, and by his merits there obtain the health you desire.” The sick man inquired, “But who are you, sir, who promise me such good things?” “What have you to do with me? Go in faith and be healed.” “Yet, sir,” persisted the pilgrim, “I beseech you do not be angry, but tell me who you are, that by the authority of your name I may be assured of the solidity of your promise.” Then the figure answered, “I am Aidan, formerly the bishop of St. Oswin, and that you may believe I will now by my touch cure this pain in your head, leaving you to be healed of you inward spasms by St. Oswin.”

So saying he pressed upon the nose of the sleeping man, and immediately a copious flow of blood took place, which relieved his head. There was a maid watching by his bed-side, and when she saw her patient covered with blood she called her mistress who, at the request of the sick man, sent for the priest of the parish. To him he related the vision, saying that Oswin he had heard a little of, but he did not so much as know the name of Aidan. As the pilgrim was unable to walk, one of the neighbors kindly offered to take him to Tynemouth in his boat. They arrived there while the monks were in chapter, and laid the sufferer at the martyr’s tomb where he was presently healed of his disease....

Once ... when Archarius was prior at Tynemouth, there dwelt there for a little while a most expert goldsmith of the name of Baldwin, whom the prior took into his service to re-gild the martyr’s shrine. St. Oswin’s day came round; there was feasting and praying and holiday at Tynemouth. Baldwin among the rest went to the feasting, and being an unsuspicious man (besides that it was St. Oswin’s day) he did not close his shop-door so carefully as he might have done. His shop was close to the church, and among the crowds a thief managed to approach it unperceived and carry away all the valuables he could lay hands on. This was a sacrilegious breach of the “Martyr’s Peace.”

The public road was open to the thief; he ran till he came to the limits of the "Peace," the border of the sanctuary, and there, though there was an open unhindered way before him, he could not move a step, but was miraculously rooted to the ground. Yet, though he could not advance, he could go here and there within the Peace as he pleased; but it was invisibly fenced, and he could not pass the bounds. However, he betook himself to a little inn within the purlieus, where, by his startled face, the levity of his deportment, and the incoherency of his speech, something was suspected, and he was arrested. Meanwhile Baldwin had become acquainted with his loss and with a heavy heart was complaining at the martyr’s tomb, when the news came that the thief had been found and his goods restored. The criminal was immediately hung, and the people feared and glorified God for the wonderful protection of St. Oswin’s Peace....

In the reign of William Rufus there was war on the Scottish border. William came to Newcastle-on-Tyne inflamed with ungovernable passion. The Scots had wasted the country all round and were then butchering old and young, priest and layman, in the poor city of Durham. William advanced, and they fled before him, for they had heard of his burning rage. Meanwhile there came fifty of William’s ships to the mouth of the Tyne, laden with corn from the West Angles to supply the king during the Scottish war. The mariners were a rude, ungodly company, and as the king had left Newcastle and there was no one to restrain them, they plundered the houses round about and did not fear to violate St. Oswin’s Peace.

There was an old woman, so weak and old that she was obliged to support herself on a staff; each year she consumed wholly with great pains and weary diligence in weaving a poor little web; it was her annual hope and harvest, and the year’s web was now lying finished by her. Whether she was walking on the shore carrying her web to sell it or whether she was in her cottage does not appear from the narrative; but at any rate she was attacked by one of the sailors, but firmly as she grasped her precious web he tore it out of her hands.

She wept and sobbed, and besought him by her patron St. Oswin and herself. The indignant old woman with much effort hobbled up to the monastery and went to the martyr’s tomb and begged him to redress her wrongs. “God,” says the monk, “who despiseth not the tears of widows, heard the old woman’s tearful sobs through the merits of the holy martyr.”

But she left the tomb dejected: No answer came to her prayers; night passed, and the web was not returned, and morning brought a fair wind. She saw the white sails proudly set and the fleet sweep down the sea towards Lindisfarne: Her web was there, her one web, her year’s livelihood; St. Oswin had not heard her prayer. The ships at length disappeared; they made a prosperous voyage to Coquet Island, a little to the north of Tynemouth. It is a rocky place, but the sea was calm and the sailors careless; and billows rose and rose, and the heavy swell thundered on the Coquet rocks. It seemed like a miracle, so tranquil, so beautiful the day. Still the sea rose, the ships were entangled among the shoals, they dashed one against another, were broken and sunk, and all hands perished.

The north wind came, and the wrecks and corpses were all drifted ashore near Tynemouth. Not a thing stolen but what the sea gave it up again faithfully, for it was doing a divine work. The cottagers had hid themselves in the woods and caves, fearing the return of the sailors. They had returned in another guise than they expected — a piteous return. Then the people left their coverts and came down to the shore, and each scrupulously confined himself to taking up what had belonged to him. Harmless on the wet sand lay a corpse with the old woman’s web in his hand; her lameness made her late, and she was among the last to receive her property. “O cruelest of men” she said to the dead sailor, “yesterday I asked you and you would not hear me; I asked my lord and patron, and he has heard me. Now you give up unwittingly the web you stole most wittingly; now you pay in death the penalty you deserved to pay when alive, because you despised the Saint in me.”

The monk draws a conclusion to this effect: Let no one think the Saints ever turn their ears from the desire of the poor; they only delay in order to answer their prayers more wonderfully. Such was a monkish doctrine in the Middle Ages; what wonder the poor so loved the monks?

ST. OSWIN’S FEAST DAY IS CELEBRATED ON AUGUST 20

Troparion of St. Oswin, Tone 1Courtesy and humility shone from thee,

O radiant Martyr Oswin.

Trained by Saint Aidan as a Christian ruler,

thou didst illumine northern Britain.

Glory to Him Who has strengthened thee;

glory to Him Who has crowned thee;

glory to Him Who through thee works healings for all.

Oswin’s Accepted Pedigree

Oswin

(d. 651)Osric

(d. 633/4)Æthelric

(d. ca. 604)Ælla (?) ? ? ? Pedigree generated by PedigreeQuery.com An Alternate Pedigree Suggested by Gordon Ward

Oswin

(d. 651)Ethelbert

(d. 616)Eormenred

(?)Eadbald Æthelbert

(1st Christian king)Eormenric ? Bertha Ymme Oslave Ermengyth (?) Pedigree generated by PedigreeQuery.com

Bibliography

Anonymous. “Vita Oswini Regis.” Miscellanea Biographica. London: J.B. Nichols & Son, 1835. 1-59.Bede. Ecclesiastical History of the English People (Revised edition). NY: Penguin, 1991.

Farmer, David Hugh. The Oxford Dictionary of Saints, 3rd edition. NY: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Moss, Vladimir. Saints of England’s Golden Age. Etna, CA: Center for Traditionalist Orthodox Studies, 1997.

Newman, John Henry. Lives of the English Saints. London: James Toovey, 1844.

Smith, Alan. Sixty Saxon Saints. Norfolk, England: Anglo-Saxon Books, 1996.

Tyson, J.C. Saint Oswin, King and Martyr. Northumberland, England: Gilpin Press, 1984.

Ward, Gordon. “King Oswin — A Forgotten Ruler of Kent.” Archaeologia Cantiana, Vol. 50 (1938): 60-65.

Return to Index